Gothic Texts Across The Ages: New Gendered Readings

Lauren Allen, Eve Hutchings and Cheryl Louis

2016

Introduction

‘Gothic novels tell terrifying stories of patriarchal societies that thrive in the oppression or even outright sacrifice of women and others.’[1] Throughout the centuries, Gothic literature has been distinguished by its engagement with social and domestic structures and how they shape the texts’ representations of both masculinity and femininity. By reviewing the emergence of Gothic literature with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), and concluding with Stephen King’s The Shining (1977), we can explore the ways in which the representations of gender within Gothic texts has both altered and, in some ways, remained faithful to the traditional ideologies depicted.

This anthology marks a journey in gender history, spanning from the eighteenth century to the twentieth century. The Castle of Otranto is assumably the conventional beginning to the Literature of the Gothic – inaugurating the Gothic tradition and therefore its tropes. ‘Since constructions of femininity and masculinity take place in relation to one another, gender widened the historical focus to include examinations of the male as well as the female experience.’[2] By combining an examination of the sexes throughout, this anthology fulfils its title of ‘Gothic texts across the ages: New gendered readings.’

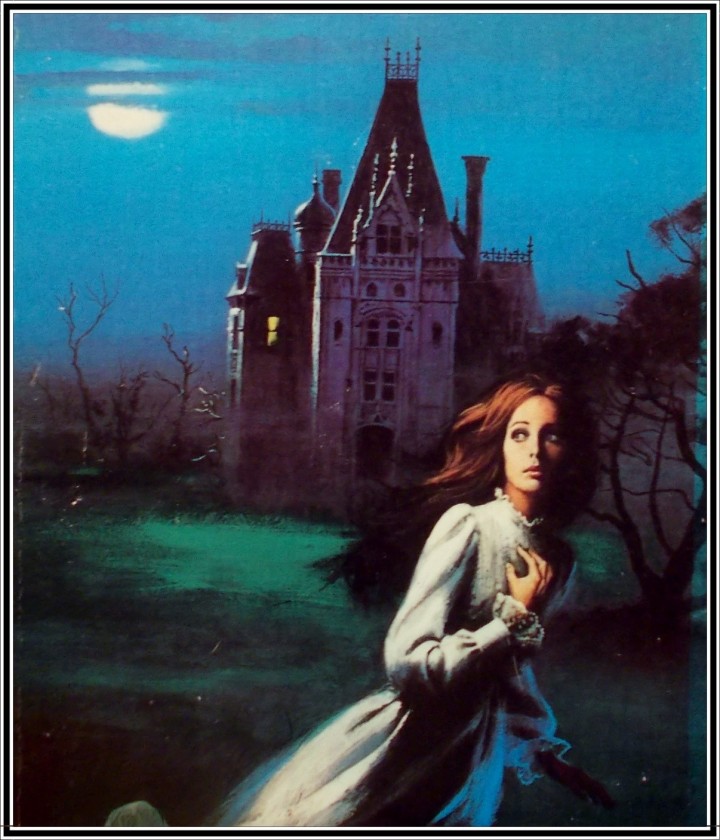

This anthology argues that the Gothic texts we have included mirror the social changes in relation to gender within the years they were published, reflecting the insecurities and anxieties of the time. Key issues include the destabilising patriarchal system, marital security, the femme fatale and the emerging ‘New Woman’. Gothic texts published during the eighteenth century tend to portray what modernist readers consider now as the stereotyped image of gender. For example, men would be portrayed in the form of villains, heroes, whereas women assumed the role of the damsel in distress. Moving into the nineteenth century, Gothic literature advanced into a new set of morals and attitudes towards gender. Now, a focus on the male gaze and the transformation of the women was at the forefront of public concern. Finally, twentieth century tales reflected an interest in the diminishing masculine identity and the emergence of the strong female. Our critical anthology highlights the ever evolving representations of gender within the Gothic canon. We aim to demonstrate the multiple responses to gender change within all spheres of society and domestic domains across the ages.

Key Terms

- Emasculation- to derive a male of his male role or identity.

- Femininity-being feminine/ having feminine qualities.

- Femme Fatale- referring to a seductive female that causes distress to others.

- Fin- De- Siècle- the time period at the end of the nineteenth century.

- Male Gaze- a male perception.

- Male hegemony- male authority/power/dominance.

- Masculinity- being masculine/having masculine qualities.

- Microcosm- a symbol for/ a small representation of something.

- Patriarchy- a social system/organisation stating male dominance.

- Sensibility- the ability to feel/feel emotion.

The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole

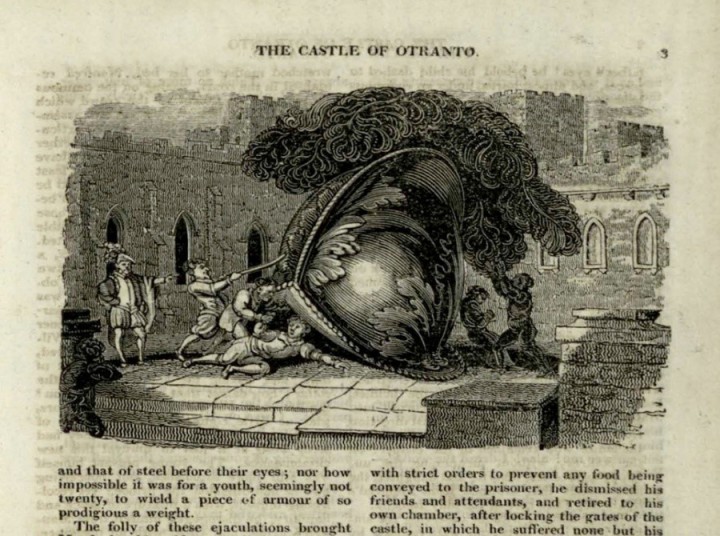

The Gothic genre emerged in the late eighteenth century, supposedly beginning with Horace Walpole’s Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto, which was published in 1764. The novel that is set during the time 1095-1243 captures the essence of tradition and medieval culture through Walpole’s use of setting and his traditional representation of gender. Walpole’s use and depiction of key Gothic elements, such as the castle, the supernatural, the representation of women as the damsel in distress figure and the men as the villainous figure, acts as an emphasis on the novels’ portrayal of the patriarchal system, the notion of women as commodities and the significance of power. According to Carol Pateman, the novel can be described as a patriarchal narrative that comments on ‘classic patriarchal societies’ and ‘the passage of power through the male line.’[3] This section of the anthology will focus on how gender has been presented by Walpole and on his depiction of the traditional view upon gender with reference to the notion of a possible destabilising of the patriarchal system.

In the eighteenth century the patriarchal structure defined both the public and private spheres, such as society and the domestic domain. Critics Hannah Barker and Elaine Chalus comment on the notion of ‘separate spheres’ and that ‘such thinking dictated that women and men were naturally suited to different spheres: for women, the ‘private sphere’ of the home and the family; for men, the ‘public sphere’ of work and politics.’ [4]Men were expected to be dominant and powerful figures, whilst women were to be meek and submissive. Walpole in his novel captures both the image of women who act as the model of femininity and men who have the authority in society. However, this text can also be seen to challenge and question society’s conventions in terms of gender equality and the roles the men and women possess.

Firstly, the function of the male characters in the novel is to be the dominant figures in control. For example, the character of Manfred, the male protagonist of the novel, can be identified as a representation of masculinity and the patriarchal system. Manfred’s character can be viewed as a traditional depiction of a villain who uses his position as a patriarch to dominate the female characters, such as Hippolita, Matilda and Isabella. Walpole, through this character, shows men’s fear of being controlled by or being inferior to the females. For example, through his use of the supernatural elements and Gothic tropes, he conveys Manfred’s actions and shows how he employs tactics, such as murder and incest to gain his power. This employment of criminality to inflict authority can be seen to indicate the previously suggested notion of a disrupted or destabilising patriarchy through the use of crime and unnecessary forces. Additionally, even the character of Theodore, who in many ways represents a hero figure rather than a villain conveys an image of the dominant male, as he shows women to be in need of rescuing. For example, Theodore near the end of the novel helps with Isabella’s escape, which both suggests dominance, but also weakness, as he betrays the patriarch figure, Manfred.

‘Manfred, Prince of Otranto, had one son and one daughter: The latter a most beautiful virgin, aged eighteen, was called Matilda. Conrad, the son, was three years younger, a homely youth, sickly, and of no promising disposition; yet he was the darling of his father, who never showed any symptoms of affection to Matilda. Manfred had contracted a marriage for his son with the Marquis of Vicenza‘s daughter, Isabella; and she had already been delivered by her guardians into the hands of Manfred, that he might celebrate the wedding as soon as Conrad‘s infirm state of health would permit. Manfred‘s impatience for this ceremonial was remarked by his family and neighbours. The former indeed, apprehending the severity of their Prince’s disposition, did not dare to utter their surmises on this precipitation. Hippolita, his wife, an amiable lady, did sometimes venture to represent the danger of marrying their only son so early, considering his great youth, and greater infirmities, but she never received any other answer than reflections on her own sterility, who had given him but one heir. His tenants and subjects were less cautious in their discourses: They attributed this hasty wedding to the Prince’s dread of seeing accomplished an ancient prophecy, which was said to have pronounced, that the Castle and Lordship of Otranto should pass from the present family, whenever the real owner should be grown too large to inhabit it. It was difficult to make any sense of this prophecy; and still less easy to conceive what it had to do with the marriage in question. Yet these mysteries, or contradictions, did not make the populace adhere the less to their opinion.’ [5]

In contrast to the men, the women’s behaviour is shown to be the result of an expectation to be obedient and, as highlighted in the extract above, it is an expectation from childhood. This is also summed up later in the novel by Hippolita herself, as she comments on the tradition of marriage and states that ‘a bad husband is better than no husband’ [6] and then later says ‘it is not ours to make election for ourselves: heaven, our fathers, and our husbands must decide for us.’ [7] Through his novel, Walpole comments on the stereotyped image of women through contrast and depicts women to be predominantly inferior and as the damsel in distress character. He mainly captures the image of subordinate females, especially through Manfred’s wife Hippolita, who agrees to divorce him for the sake of the castle and to meet his desire of being an heir: ‘I will go and offer myself to this divorce-it boots not what becomes of me. I will withdraw into the neighbouring monastery and waste the remainder of life in prayers and tears for my child and –the Prince.’ [8] Also, as shown in the extract above, Hippolita is completely expected to do what she is told. However, Manfred doesn’t end his manipulations here with just Hippolita, as his next conquest is to marry fifteen year old Isabella who was originally ‘contracted’ [9] to marry his deceased son in order to form a familial connection to the heirs of the castle, which is also outlined in the extract above from chapter one. This extract has been taken from the very first paragraph of chapter one and has been chosen to specifically highlight the elements of tradition, marriage and patriarchy. Additionally, the quotations referred to in this section show how the Gothic trope of the castle which is shown to be the main setting, can even be interpreted as a character of its own and can be seen to represent and further emphasis the image of power and suggests wealth, class and authority. The castle embodies all the qualities men aspire to possess, which is also an idea that coincides with the eighteenth century rise of the middle-class England.

‘Words cannot paint the horror of the Princess’s situation. Alone in so dismal a place, her mind imprinted with all the terrible events of the day, hopeless of escaping, expecting every moment the arrival of Manfred, and far from tranquil on knowing she was within reach of somebody, she knew not whom, who for some cause seemed concealed thereabouts, all these thoughts crowded on her distracted mind, and she was ready to sink under her apprehensions. She addressed herself to every Saint in heaven, and inwardly implored their assistance. For a considerable time she remained in an agony of despair. At last, as softly as was possible, she felt for the door, and having found it, entered trembling into the vault from whence she had heard the sigh and steps. It gave her a kind of momentary joy to perceive an imperfect ray of clouded moonshine gleam from the roof of the vault, which seemed to be fallen in, and from whence hung a fragment of earth or building, she could not distinguish which, that appeared to have been crushed inwards. She advanced eagerly towards this chasm, when she discerned a human form standing close against the wall.’ [10]

Conversely, the extract above even though it highlights Isabella’s fear of Manfred and the system, it also conveys an image of courage, as she contemplates the idea of escape. Courage and female strength are highlighted through the image of the door and this notion of the external world. Additionally, Isabella’s later rejection to the marriage proposal and her escape using her own initiative suggests that Walpole is both conforming, yet challenging traditional representations of gender. Isabella, though depicted as a vulnerable female at the beginning of the novel, ‘Then shutting the door impetuously, he flung himself upon a bench against the wall, and bade Isabella sit by him. She obeyed trembling,’ [11] goes against her stereotype and later transforms into an independent character who could symbolise Walpole’s attempt to try something new, in terms of genre and his portrayal of gender representations. Additionally, Isabella escapes being murdered by Manfred as he mistakes his own daughter for her and ultimately Matilda dies by her own father’s hand, which both adds to Manfred’s villainous persona and highlights the patriarchal systems possible weaknesses.

‘I shall not dwell on what is needless. The daughter of which Victoria was delivered, was at her maturity bestowed in marriage on me. Victoria died; and the secret remained locked in my breast. Theodore’s narrative has told the rest.

The Friar ceased. The disconsolate company retired to the remaining part of the castle. In the morning Manfred signed his abdication of the principality, with the approbation of Hippolita, and each took on them the habit of religion in the neighbouring convents. Frederic offered his daughter to the new Prince, which Hippolita’s tenderness for Isabella concurred to promote. But Theodore’s grief was too fresh to admit the thought of another love; and it was not until after frequent discourses with Isabella of his dear Matilda, that he was persuaded he could know no happiness but in the society of one with whom he could for ever indulge the melancholy that had taken possession of his soul.’ [12]

Overall, The Castle of Otranto comments on traditional society through the depiction of heroes, villains and the damsel in distress figures. Through these created stereotypes Walpole highlights how this is a novel that predominantly deals with patriarchal dominance and yet exposes the male anxieties of female dominance. According to John Brown, ‘clearly defined gender roles were central to the stability of English society, and by extension, to England’s status as a world power.’ [13] Walpole, through his novel, attempts to remain conventional in his depiction of gender representations with the symbols of marriage and property. However, as shown in the extract above, the story even though told as a male narrative, highlights male weaknesses through the depiction of grief and emotion. Additionally, through his use of supernatural occurrences, like the falling helmet that kills Manfred’s son, he over-exaggerates and ultimately challenges and questions the true stability of the patriarchal structure and the inferior position of women.

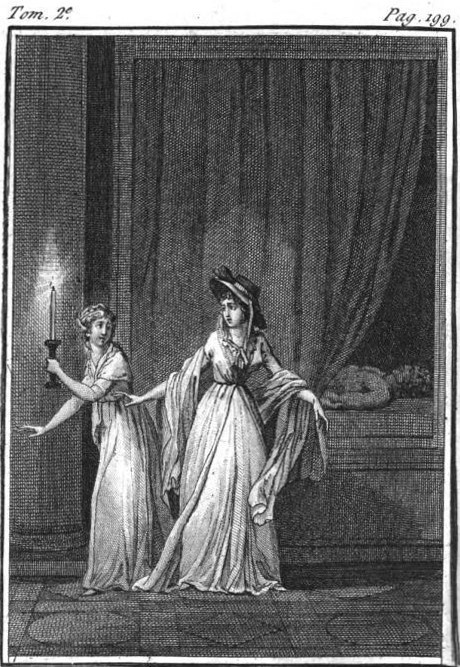

The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) by Ann Radcliffe

The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) by Ann Radcliffe precedes Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto and is a novel that similarly highlights the cultural politics of gender in the late eighteenth century, whilst showing how the issue of femininity and masculinity is a key concept of Gothic Literature. Radcliffe uses the Gothic genre to emphasis and criticise the point of study in the patriarchal structure. As a female writer Radcliffe can be described as proto-feminist through her need to portray women as the triumphant figures in her novels. According to Ellen Moers, Radcliffe was central in shaping the idea of the ‘female gothic’ and states that the sub-genre is one which a ‘woman is examined with a woman’s eye.’ [14] This section of the anthology will focus on how The Mysteries of Udolpho can be viewed as a text that criticises gender representations of the time and ultimately offers an alternative notion to the dominant patriarchal system which although is challenged, is more religiously followed in Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto.

Firstly, the death of the matriarch and patriarch early on in the novel ultimately becomes the catalyst to the events that later occur, such as Emily’s imprisonment in the castle. The death of Emily’s mother and father, the owner of property and wealth has been outlined by including an extract later on in this essay. Radcliffe through this event shows how once the patriarch has died and been removed, other males such as Montoni, begin to feel inferior, especially when Emily is in line to become heiress of his estate and fortune. This idea highlights the idea of property and money representing status and power. Moreover, through this, the beginning of the novel emphasises societies and individuals dependence on the male species, as Radcliffe shows how the domestic domain destabilises once the patriarch is removed. However, the novel transforms into a text that conveys this idea of a female domain through the character of Emily and can possibly be described as a bildungsroman novel that focuses on the progress and development of the heroine.

Radcliffe both represents the old and new ideologies of femininity within her text. Firstly, she comments on traditional gender roles through the character of Emily who is portrayed as a heroine imprisoned in a castle. The image of the castle can be seen to act as a symbol of power and is used as a microcosm of male hegemony in society (a symbol for male authority). In the novel, the male figures attempt to weaken the female characters by stripping them of their senses by leaving them trapped and cut off from the outside world. Similarly to Walpole, Radcliffe adopts this Gothic trope to represent authority and the idea of oppression. However, Radcliffe at the same time uses the castle as a symbol of isolation and madness, for both the males and the females in the novel. Her employment of Gothic tropes and her use of scenery and setting adds to the oppression and ultimately contributes to the idea of madness. For example, the women within the castle such as Emily and her Aunt are being denied access to the external world and are surrounded by dominating men: ‘this man, with another, whose face betrayed either the consciousness of guilt, or the fear of punishment…’ [15] This quotation further highlights the male dominance and the women’s feeling of fear and entrapment.

Moreover, Radcliffe, through her depiction of the male characters, seems to be criticising the male traits and overall the eighteenth century male figure. Apart from the character of Emily’s father, the male characters such as Montoni, Count Morano and even Valencourt are portrayed as greedy and power hungry figures. As Emily says:

‘There is some magic in wealth, which can thus make persons pay their court to it, when it does not even benefit themselves. How strange it is, that a fool or a knave, with riches, should be treated with more respect by the world, than a good man, or a wise man in poverty!’ [16]

For example, Montoni’s interest in Emily’s Aunt Madame Cheron and Emily herself, is purely to attain her property and inheritance. Additionally, Count Morano is also a part of Montoni’s plans and, as well as subjecting the women to imprisonment, a traditional aspect is employed to suppress the women further. Radcliffe’s reference to marriage such as the marriage between Emily’s aunt and Montoni and the proposal between Count Morano and Emily is an example of how society’s concentration is on a patriarchal system which controls women.

‘The physician was affected; he promised to obey her, and told St. Aubert, somewhat abruptly, that there was nothing to expect. The latter was not philosopher enough to restrain his feelings when he received this information; but a consideration of the increased affliction which the observance of his grief would occasion his wife, enabled him, after some time, to command himself in her presence. Emily was at first overwhelmed with the intelligence; then, deluded by the strength of her wishes, a hope sprung up in her mind that her mother would yet recover, and to this she pertinaciously adhered almost to the last hour.

The progress of this disorder was marked, on the side of Madame St. Aubert, by patient suffering, and subjected wishes. The composure, with which she awaited her death, could be derived only from the retrospect of a life governed, as far as human frailty permits, by a consciousness of being always in the presence of the Deity, and by the hope of a higher world. But her piety could not entirely subdue the grief of parting from those whom she so dearly loved. During these her last hours, she conversed much with St. Aubert and Emily, on the prospect of futurity, and on other religious topics. The resignation she expressed, with the firm hope of meeting in a future world the friends she left in this, and the effort which sometimes appeared to conceal her sorrow at this temporary separation, frequently affected St. Aubert so much as to oblige him to leave the room. Having indulged his tears awhile, he would dry them and return to the chamber with a countenance composed by an endeavour which did but increase his grief.

Never had Emily felt the importance of the lessons, which had taught her to restrain her sensibility, so much as in these moments, and never had she practised them with a triumph so complete. But when the last was over, she sunk at once under the pressure of her sorrow, and then perceived that it was hope, as well as fortitude, which had hitherto supported her. St. Aubert was for a time too devoid of comfort himself to bestow any on his daughter.’[17]

Conversely, ‘the second half of the eighteenth century has long been known as the “age of sensibility”, with “sensibility referring to a capacity for strong and generally sympathetic feeling.’ [18] The extract above gives an example of this and outlines the importance of females being in control of their own sensibility through the death of Emily’s mother. Radcliffe, throughout the novel, shows the female characters to have one prominent strength which is their ability to control their emotions. Before Emily’s mother and father died they gave her some advice which warned her to avoid ‘ill-governed sensibility,’ which can leave you open to being ‘victims of our feelings, unless we can in some degree command them.’ [19] By this, her father can be interpreted to mean, remain strong and avoid excessive emotions, as he further states ‘how much more valuable is the strength of fortitude, than the grace of sensibility . . . Remember too, that one act of beneficence, one act of real usefulness, is worth all the abstract sentiment in the world.’ [20] Throughout the novel Emily is able to stay in control by controlling her emotions which ultimately becomes her strength, even when she is overwhelmed or Montoni is purposely creating terrors, as his aim is to terrify her into marrying Count Morano after she first refuses him. Additionally, the novel concludes with the success of Emily, as at the end, she is able to make her own decision of selling the estate inherited from her aunt and Laurentini and resides in her father’s home. Even though by remaining faithful to her father’s wishes Emily is somewhat serving to a patriarch, she remains independent and in control. This female success and strength is further conveyed in the extract below and is in support of Radcliffe’s attempt at creating an alternative notion to the dominant patriarchy.

‘The legacy, which had been bequeathed to Emily by Signora Laurentini, she begged Valancourt would allow her to resign to Mons. Bonnac; and Valancourt, when she made the request, felt all the value of the compliment it conveyed. The castle of Udolpho, also, descended to the wife of Mons. Bonnac, who was the nearest surviving relation of the house of that name, and thus affluence restored his long-oppressed spirits to peace, and his family to comfort.

O! how joyful it is to tell of happiness, such as that of Valancourt and Emily; to relate, that, after suffering under the oppression of the vicious and the disdain of the weak, they were, at length, restored to each other—to the beloved landscapes of their native country,—to the securest felicity of this life, that of aspiring to moral and labouring for intellectual improvement—to the pleasures of enlightened society, and to the exercise of the benevolence, which had always animated their hearts; while the bowers of La Vallee became, once more, the retreat of goodness, wisdom and domestic blessedness!

O! Useful may it be to have shewn, that, though the vicious can sometimes pour affliction upon the good, their power is transient and their punishment certain; and that innocence, though oppressed by injustice, shall, supported by patience, finally triumph over misfortune!

And, if the weak hand, that has recorded this tale, has, by its scenes, beguiled the mourner of one hour of sorrow, or, by its moral, taught him to sustain it—the effort, however humble, has not been vain, nor is the writer unrewarded.’

Overall, Radcliffe conveys the image of strong females and the notion of success of being in control of the self, rather than what you own. The novel focuses on the heroines and the female characters development, even after their parents have died. Additionally, Radcliffe, throughout this novel, explores the possibilities for women in a patriarchal society, in terms of property and inheritance. However, it seems ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho suggests that the way for a woman to escape the Gothic nightmare of patriarchal society is – ironically – through identification with the patriarch’ [22]which is shown through the character of Emily and her identification with her father and his memory. Finally, the issues of femininity and masculinity are thus key concerns of the Gothic genre, in terms of boundaries and the gender divide. However, Radcliffe suggests alternatives through creating a female domain and with her references to ‘sensibility’ potentially ‘levelling the ground between men and women.’ [23]

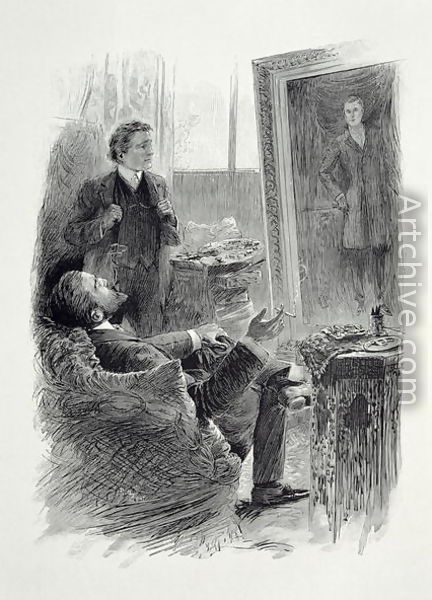

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) by Oscar Wilde

‘I turned half-way round, and saw Dorian Gray for the first time. When our eyes met, I felt that I was growing pale. A curious sensation of terror came over me, I knew that I had come face to face with someone whose mere personality was so fascinating that, if I allowed it to do so, it would absorb my whole nature, my whole soul, my very art itself.’[24]

Gendered readings of Oscar Wilde’s Gothic novel The Picture of Dorian Gray are complex, In this analysis, we shall focus upon the ways in which the novel reflects the changes that conventional codes of the Victorian gentleman underwent during the late nineteenth century and the altered male status and identity. This analysis will also focus on the ways in which the novel represents women.

It is however, important to gain an understanding of the time period in which Wilde was writing as the end of the nineteenth- century was an incredibly turbulent time in terms of gender politics and gender identity. When analysing Victorian Gothic literature, this period of time at the turn of the century is referred to as “fin de siècle” which also summarises a time that oversaw a new set of artistic, moral, and social concerns and movements. When reading The Picture of Dorian Gray in terms of gender, it is essential to understand that it was written in the midst of many social changes as masculine and feminine constructs underwent many transformations.

Andrew Smith argues masculinity was forced to undergo transformations in order to compensate for the loss of old traditional forms of masculinity ‘men sought to establish new masculine identities which operated beyond the traditional, patriarchal domestic spaces.’[25] The Picture of Dorian Gray can be interpreted in a way that highlights the negative aspects of a new masculine identity ‘we can isolate a specific narrative that within the literature of the fin-de-siècle which illuminates how masculinity becomes associated with disease, insanity and perversion.’[26] This anxiety surrounding a changing male identity is hinted at in the passage below by Lady Narborough: (294)

‘If we women did not love you for your defects, where would you all be? Not one of you would be married. You would be a set of unfortunate bachelors. Not, however, that that would alter you much. Nowadays all men live like bachelors, and all bachelors like married men.’

‘Fin de siècle,’ murmured Lord Henry.

‘Fin du globe’ answered his hostess.

‘I wish it were fin du globe,’ said Dorian, with a sigh. ‘Life is a great disappointment.’[27]

Here, Lady Narborough is draws attention to the fact that men have begun to reject their traditional gender roles as fathers and husbands. The roles of the provider of the house and their marital duties are beginning to diminish. ‘In Wilde’s novel these images of social disarray reflect on the home, in which the end of the family is also the end of the world.’[28] Consider that the trio of men in the novel, Dorian Gray, Basil Hallward and Sir Henry Wotton are either bachelors or, in the case of Sir Henry, live as bachelors. There is a distinct lack of men with marital or family responsibilities. Sir Henry’s relationship with his wife best portrays the idea that men are dismissive of their domestic roles, and his wife has been written into the story simply as a decorative prop. A gentleman of high society must have a wife and Henry’s unnamed wife serves this purpose. The marriage is virtually non-existent and purely functional.

‘I never know where my wife is, and my wife never knows what I am doing. When we meet – we do meet occasionally, when we dine out together, or go down to the Duke´s – we tell each other the most absurd stories with the most serious faces. My wife is very good at it – much better, in fact, than I am. She never gets confused over her dates, and I always do. But when she finds me out, she makes no row at all […] she merely laughs at me.’[29]

In terms of women, The Picture of Dorian Gray also contains issues surrounding the social status and representation of women. In particular, the novel contains many examples of the representation of women from the perspective of men. The novel can be argued to be a work that emphasises the male gaze. For example, female characters are frequently objectified and sexualised, admired only for their beauty and defined by their roles within society. Wilde confines women to their roles of mothers, wives, housekeepers and prostitutes, ultimately acting as aids to men. Women are still considered the decorative sex and consequently, misrepresented.

The Picture of Dorian Gray exhibits women within the cages in which they are held, defined only by their gender roles. Moreover, there is very little evidence of an identity outside the roles in which they are positioned. For example, the only passage that is dedicated to the perspective of a woman is Sybil Vane’s short narrative in which she is overcome by her lust and love for Dorian or ‘Prince Charming’ as she refers to him as. Her story is dominated by her naïve perception that Dorian and she will live happily ever after. Her character development reveals little else. Indeed the novel is very much concerned with the masculine depiction of the opposite gender, highlighting male perceptions and is therefore limited as the passage below from Sir Henry’s point of view on women demonstrates:

“I am afraid that women appreciate cruelty, downright cruelty, more than anything else. They have wonderfully primitive instincts. We have emancipated them, but they remain slaves looking for their masters, all the same. They love being dominated.”[30]

The character of Sybil Vane is highly significant when analysing the novel from a feminist perspective. Her profession as an actress in the theatre is symbolic as she is permanently placed within the male gaze. As she is an actress, it is also important to consider the Sybil Vane is only represented through the impersonation of other fictional women Night after night, Dorian goes to the theatre to see Sybil perform as Shakespearian heroines and is enraptured by her ability to transform into romantic figures such as Juliet, Ophelia and Desdemona. This is significant because Dorian does not fall in love with the real Sybil Vane, but rather a fantastical and idealised version of her. Rather like the portrait, her beauty has fixated him. However, as mentioned earlier, Dorian is obsessed with the aesthetic, falling in love with Sybil based upon on her appearance alone and her ability to masquerade as romantic heroines of Shakespearian tragedies. Dorian is captivated by beauty of Sybil, but her soul is irrelevant to him. His description of Sybil to Henry is evidence of the objectification of Sybil ‘I love Sibyl Vane. I want to place her on a pedestal of gold, and to see the world worship a woman who is mine.’[31] This obsession however ends abruptly. The night that she decides she cannot possibly pretend to love another on stage, is the night he bitterly rejects her and reveals that he is disgusted by her inability to perform and her falsehood. When Dorian leaves the theatre and Sybil, she commits suicide.

This passage follows the aftermath of Sybil Vane’s death and Dorian’s reaction to her suicide. It is a significant section of the novel because it demonstrates the way in which Dorian tries to romanticise her suicide to distance himself from guilt. It reduces the death of a woman into a piece of romantic fiction.

“You said to me that Sybil Vane represented to you all the heroines of romance – that she was Desdemona one night, and Ophelia the other; that if she died as Juliet, she came to life as Imogen.”

“She will never come to life again now,” muttered the lad, burying his face in his hands.

“No, she will never come to life. She has played her last part. But you must think of that lonely death in the tawdry dressing-room simply as a strange lurid fragment from some Jacobean tragedy, as a wonderful scene from Webster, or Ford, or Cyril Tourneur. The girl never really lived, and so she never really died. To you at least she was always a dream, a phantom that flitted through Shakespeare’s plays and left them lovelier for its presence a reed through which Shakespeare’s music sounded richer and more full of joy. The moment she touched actual life, she marred it, and it marred her, and so she passed away. Mourn for Ophelia, if you like. Put ashes on your head because Cordelia was strangled. Cry out against Heaven because the daughter of Brabantio died. But don’t waste your tears over Sybil Vane. She was less real than they are.”

After some time Dorian Gray looked up. “You have explained me to myself Harry,” He murmured, with something of a sigh of relief. “I felt all that you have said, but somehow I was afraid of it, and I could not express myself. How well you know me! But we will not talk again of what has happened. It has been a marvellous experience. That is all.”[32]

Anderson argues that Dorian is guilty of ‘negating Sibyl’s humanity and feeding upon the sensual and artistic catharsis he gives to her suicide. Reminiscent of the nitric acid that Campbell uses to dissolve Basil’s body, Sibyl commits suicide by taking “prussic acid” dissolving her presence from the novel.’[33] Indeed, Dorian cruelly extinguishes Sybil completely and quickly immerses himself in other pleasures.

DRACULA (1897) by Bram Stoker

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) is a classic text within the realms of Gothic literature and exists as one which concentrates on ‘the strong feminine appeal of the vampire which has received far less attention than the masculine concerns that the vampire is said to raise’[34]. With the novel being originally published at the turn of the twentieth century, anxieties existed within British society regarding what the new century may bring. For example, patriarchal dominance was beginning to be questioned and, hence, raised the idea of the ‘New Woman’. Those of traditional thinking believed that the ‘New Woman’ entailed a certain ‘permissiveness undermined social stability by breaking down the vital bonds of state and culture and by inciting selfish behaviour’[35]. Although uninformed hysteria such as this occurred, today we understand the ‘New Woman’ to be a female who has decided to become involved in ‘rejecting the hierarchy and gender polarities’[36] that society insisted upon, and instead choosing to be independent, being in charge of the outcomes of her own life and feeling sexually and socially liberated to marry and have sexual relations with who she pleases. In this way, Stoker’s Dracula can be thought of as a response and a representation of the opposing opinions regarding the ‘New Woman’ due to his use of the three female vampires and that of Lucy Westenra – of whom rejects three marriage proposals throughout the novel – as creatures of sexual liberation. Mina Murray, who becomes Mina Harker after her marriage to Jonathan, can also be thought of as a ‘New Woman’, with her interest in not only the advancements of technology, but also science and education in general. However, by both Lucy and the group of female vampires ultimately being punished, we can understand Stoker’s representation of the liberated woman as misogynistic, as they cannot be seen to be the heroines of the novel.

‘I was not alone. The room was the same, unchanged in any way since I came into it; I could see along the floor, in the brilliant moonlight, my own footsteps marked where I had disturbed the long accumulation of dust. In the moonlight opposite me were three young women, ladies by their dress and manner. I thought at the time that I must be dreaming when I saw them, for, though the moonlight was behind them, they threw no shadow on the floor. They came close to me and looked at me for some time, and then whispered together. Two were dark, and had high aquiline noses, like the Count, and great dark, piercing eyes, that seemed to be almost red when contrasted with the pale yellow moon. The other was fair, as fair can be, with great masses of golden hair and eyes like pale sapphires. I seemed somehow to know her face, and to know it in connection with some dreamy fear, but I could not recollect at the moment how or where. All three had brilliant white teeth that shone like pearls against the ruby of their voluptuous lips. There was something about them that made me uneasy, some longing and at the same time some deadly fear. I felt in my heart a wicked, burning desire that they would kiss me with those red lips. It is not good to note this down, lest someday it should meet Mina’s eyes and cause her pain, but it is the truth. They whispered together, and then all three laughed, but as hard as though the sound never could have come through the softness of human lips. It was like the intolerable, tingling sweetness of waterglasses when played on by a cunning hand. The fair girl shook her head coquettishly, and the other two urged her on. One said:

‘Go on! You are first, and we shall follow. Yours is the right to begin.’ The other added:

‘He is young and strong. There are kisses for us all.’ I lay quiet, looking out from under my eyelashes in an agony of delightful anticipation. The fair girl advanced and bent over me till I could feel the movement of her breath upon me. Sweet it was in one sense, honey-sweet, and sent the same tingling through the nerves as her voice, but with a bitter offensiveness, as one smells in blood.

I was afraid to raise my eyelids, but looked out and saw perfectly under the lashes. The girl went on her knees, and bent over me, simply gloating. There was a deliberate voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive, and as she arched her neck she actually licked her lips like an animal, till I could see in the moonlight the moisture shining on the scarlet lips and on the red tongue as it lapped the white sharp teeth. Lower and lower went her head as the lips went below the range of my mouth and chin and seemed to fasten on my throat. Then she paused, and I could hear the churning sound of her tongue as it licked her teeth and lips, and I could feel the hot breath on my neck. Then the skin of my throat began to tingle as one’s flesh does when the hand that is to tickle it approaches nearer, nearer. I could feel the soft, shivering touch of the lips on the super sensitive skin of my throat, and the hard dents of two sharp teeth, just touching and pausing there. I closed my eyes in languorous ecstasy and waited, waited with beating heart.

But at that instant, another sensation swept through me as quick as lightning. I was conscious of the presence of the Count, and of his being as if lapped in a storm of fury, the white teeth champing with rage, and the fair cheeks blazing red with passion. But the Count! Never did I imagine such wrath and fury, even to the demons of the pit.’ [37]

The narrative viewpoint of Jonathan Harker as presented within Stoker’s Dracula is written in the form of a diary, and is therefore written in the first person, creating an intimacy between the character who is narrating and the reader of the text. We are able to understand his perspective through a series of diary entries which are a confessional form of writing. This personal tone allows the concept of vampires to feel more plausible by being written as an account of supposedly true events. However, it is important for us as readers to remain aware that Jonathan’s narrative may be bias as we are only given access to one character’s point of view, and therefore his retelling of the events of the novel may be unreliable.

‘In the moonlight opposite me were three young women, ladies by their dress and manner’[38]

Throughout this extract, we can clearly see the typical Gothic ideas and tropes that were prominent within Victorian Gothic literature, as Stoker is oppressively vivid with his use of Gothic imagery. For example, the above extract sets the scene with the following sentence: ‘I was not alone.’[39] We immediately know that Jonathan is in danger as he has entered the part of the castle that Count Dracula warned would not be safe. This isolation creates tension and suspense, with readers possibly fearing for the safety of the narrator. Jonathan also records the presence of ‘the pale yellow moon’[40] and, as being under the cover of moonlight is a typical Gothic setting, readers are presupposing that an unfortunate occurrence is imminent. He is promptly approached by three women who ‘threw no shadow on the floor’[41], which is a classic trope used throughout Gothic literature, allowing us to question as to whether the women are of supernatural origins or if they are simply a figment of Jonathan’s distressed imagination. Jonathan’s account also focusses on the colour red on several occasions, with mentions of ‘the ruby of their voluptuous lips’ [42] and regarding ‘the moisture shining on the scarlet lips and on the red tongue’[43]. In terms of imagery associated with the colour red, Jonathan is experiencing a concoction of danger and desire and is therefore unsure how to feel about the three women as he is consistently crossing boundaries throughout the extract between being trapped within their seduction and being repulsed by the forwardness of their sexuality. Jonathan’s uneasiness regarding reality and overactive perceptions permits readers to consider whether Jonathan has encountered an unfortunate situation or there has been a significant impact on his psychological state due to the seclusion Jonathan is experiencing within Count Dracula’s castle.

‘[T]he sexual desires dramatised in the novel take the symbolic form of vampires because of the sexual repression of the Victorian age’[44]

Within literature, it is a common occurrence for women to be subject to the male gaze and objectification. However, within Stoker’s Dracula, a novel of vampiric eroticism, and with the extract presented above in mind specifically, it is Jonathan who exists as the primary object of desire, with the three female vampires representing Jonathan’s fear of desire, as he attempts to resists their advances. Stoker does manage to present the three women in a sexualised manner, though, referring to ‘the ruby of their voluptuous lips’[45], drawing obvious attention to their mouths, creating a sensuous atmosphere within this scene. Despite Jonathan articulating fear, he expresses a ‘burning desire’ that the women would kiss him, suggesting that, in truth, he wants to be corrupted by them. According to critic Milly Williamson, ‘what men really fear is active female sexuality and the vampires in Dracula symbolise that fear’[46] and, therefore, what Jonathan is afraid of is the women being in control of their sexuality. The women discuss Jonathan as though he cannot hear them, with one of the women stating that there will be ‘kisses for us all’[47], which only emphasises their predatory nature further.

‘I was afraid to raise my eyelids’ [48]

As we move on through the extract, we learn that Jonathan is becoming increasingly submissive towards the women, creating a role reversal in terms of the original stereotypes between the sexes. In this passage from Stoker’s Dracula, it is the male who exists within the passive role of the two genders, whilst the women are presented as sexually deviant. ‘The girl went on her knees, and bent over’ Jonathan, with a ‘deliberate voluptuousness’[49]. It is quite evident that this passage is highly sexual and, as we have already discussed, the Victorian era existed as being very sexually suppressed. Therefore, because Stoker could not write about sex freely within this period, he used the three female vampires – and Lucy Westenra during her transformation into a vampire – as a way of expressing sexuality but also concealing it to avoid criticism. The highly descriptive sexual imagery that is inevasible throughout the above passage increases in tension as Jonathan’s account of his own emotions becomes more vivid: ‘I closed my eyes in languorous ecstasy and waited, waited with beating heart’[50] .The increase in tension is essentially overwhelming for Jonathan and the intense language used allows readers to experience a similar stifling atmosphere to that of the narrator. This climax is ultimately released as Count Dracula returns to interrupt the incident by violently removing the women from Jonathan, reversing the gender roles back as the Count gains the ultimate power by defusing the women’s potential seduction. By physically assaulting the three vampires, Count Dracula has punished them for their sexual promiscuity, as Stoker cannot allow his female characters to be rewarded for sexual emancipation.

Bibliography

Barker, Hannah and Chalus, Elaine, Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representations and Responsibilities, United Kingdom: Addison Wesley Longman Limited, 1997.

Heiland, Donna, Gothic and Gender: An introduction, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004.

Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Rogers, David, ‘Introduction’ in Bram Stoker, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000.

Smith, Andrew, Victorian Demons Medicine, Masculinity and the Gothic at the Fin-de-Siècle, Manchester University Press.

Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000.

Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p110.

Wilde, Oscar, The Picture of Dorian Gray, W.W Norton & Company 2007.

Williamson, Milly, The Lure of the Vampire, London: Wallflower Press, 2005.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/christopher-lee-obituary-actor-dies-at-the-age-of-93-after-an-illustrious-and-diverse-career-10313046.html#gallery) (Accessed: 12/03/2016)

http://nerdist.com/nbc-developing-new-series-based-on-draculas-brides/(Accessed: 12/03/2016)

http://byronofrochdale.tumblr.com/post/43092066864/artemisialafee-but-first-on-earth-as-vampire(Accessed: 12/03/2016)

https://standrewsrarebooks.wordpress.com/2015/02/19/reading-the-collections-week-3-the-castle-of-otranto/ (Accessed: 12/03/2016)

http://audiodrama.wikia.com/wiki/The_Castle_of_Otranto (Accessed: 12/03/2016)

http://womanandhersphere.com/tag/mysteries-of-udolpho/ (Accessed: 12/03/2016)

http://www.gothic.stir.ac.uk/blog/ann-radcliffes-the-mysteries-of-udolpho-an-adaptation-for-television/ (Accessed: 12/03/2016)

https://eighteenthcenturylit.wordpress.com/character-setting-and-story/characters/ (12/03/2016)

http://www.artchive.com/web_gallery/A/(after)-Thiriat,-Paul/Illustration-from-The-Picture-of-Dorian-Gray-by-Oscar-Wilde-1854-1900,-engraved-by-E.-d’Ete-2.html(Accessed: 12/03/2016)

https://hauntedhearts.wordpress.com/ (Accessed 12/03/2016)

[1] Heiland, Donna, Gothic and Gender: An Introduction, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004, back cover.

[2] Barker, Hannah, Chalus, Elaine, Gender in Eighteenth Century England: Roles, Representations and Responsibilities, United Kingdom: Addison Wesley Longman, 1997, p.6.

[3] Heiland, Donna, Gothic and Gender: An introduction, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004, p 12.

[4] Barker, Hannah and Chalus, Elaine, Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representations and Responsibilities, United Kingdom: Addison Wesley Longman Limited, 1997, p11.

[5] Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p15.

[6] Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p38.

[7] Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p88.

[8] Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p87.

[9] Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p27.

[10] Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p22-23.

[11] Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p22.

[12] Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto, ed. W.S. Lewis, London: Oxford University Press, 1964, p110.

[13] Barker, Hannah and Chalus, Elaine, Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representations and Responsibilities, United Kingdom: Addison Wesley Longman Limited, 1997, p1.

[14] Heiland, Donna, Gothic and Gender: An introduction, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004, p57.

[15] Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, London: Oxford University Press, 1970, p313.

[16] Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, London: Oxford University Press, 1970, p587.

[17] Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, London: Oxford University Press, 1970, p19.

[18] Heiland, Donna, Gothic and Gender: An introduction, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004, p11.

[19] Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, London: Oxford University Press, 1970, p80.

[20] Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, London: Oxford University Press, 1970, p80.

[21] Radcliffe, Ann, The Mysteries of Udolpho, London: Oxford University Press, 1970, p627.

[22] Heiland, Donna, Gothic and Gender: An introduction, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004, p76.

[23] Heiland, Donna, Gothic and Gender: An introduction, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004, p11.

[24] Wilde, Oscar, The Picture of Dorian Gray, W.W Norton & Company, 2007, p.10

[25] Smith, Andrew, Victorian Demons Medicine, Masculinity and the Gothic at the Fin-de-Siècle Manchester University Press p.2

[26] Smith, Andrew Victorian Demons Medicine, Masculinity and the Gothic at the Fin-de-Siècle Manchester University Press p.166

[27] Wilde, Oscar, The Picture of Dorian Gray, W.W Norton & Company 2007, p.149

[28] Smith, Andrew, Victorian Demons Medicine, Masculinity and the Gothic at the Fin-de-Siècle, Manchester University Press, p.167

[29] Wilde, Oscar, The Picture of Dorian Gray, W.W Norton & Company 2007, p.8

[30] Wilde, Oscar, The Picture of Dorian Gray, W.W Norton & Company 2007, p.86

[31] Wilde, Oscar, The Picture of Dorian Gray, W.W Norton & Company 2007, p.66

[32] Wilde, Oscar, The Picture of Dorian Gray, W.W Norton & Company 2007, pp.86-7

[33] Anderson, MR 2008, ‘Wilde’s Dorian Gray as Aesthetic Vampire’, POMPA: Publications Of The Mississippi Philological Association, pp. 157-164, Humanities International Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 9 March 2016.

[34] Williamson, Milly, The Lure of the Vampire, London: Wallflower Press, 2005, pp. 2

[35] Rogers, David, ‘Introduction’ in Bram Stoker, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. xii

[36] Rogers, David, ‘Introduction’ in Bram Stoker, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp.xiii

[37] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33-34

[38] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[39] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[40] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[41] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[42] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[43] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[44] Williamson, Milly, The Lure of the Vampire, London: Wallflower Press, 2005, pp. 8

[45] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[46] Williamson, Milly, The Lure of the Vampire, London: Wallflower Press, 2005, pp. 11

[47] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[48] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[49] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 33

[50] Stoker, Bram, Dracula, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 2000, pp. 34